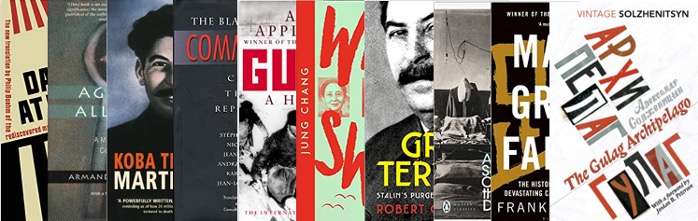

Around the corner from me is a barber’s shop decorated with black and white photographs of icons of the 20th century. James Dean is there with a cigarette hanging out of his mouth. Marilyn Munroe is perching on the edge of a pool table. A poster for the film, Taxi Driver, is alongside a photo of Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack. In among these are Che Guevara and Lenin.

I guess the aim is to appear edgy, alternative and rebellious. But obviously there is no image of Hitler. That would be unacceptable. Hitler was a fascist who invaded countries and killed millions of people. It would be tasteless to display an image of him. But Guevara and Lenin are apparently O.K.

This Sunday is the centenary of the death of Lenin and I asked Whitestone Insight to do an opinion poll to discover what people think of him. It emerges that a lot of young people like Lenin.

The poll revealed that 15 per cent of those aged between 18 and 24 have a favourable or very favourable view of him. That is compared with only three per cent of those over 65. Among the young who have heard of Lenin and have a view one way or the other, the proportion who approve of him rises to 42 per cent. Many young people are keen on communism in general, too, with 24 per cent having a favourable view of it. And it is very clear that the longer young people are exposed to higher education, the more likely they are to be pro-Lenin and pro-communist.

All this chimes with a vox pop we filmed a few weeks ago outside the School of African and Asian Studies in London. A mature woman, surely a lecturer, emerged from the building and boldly asserted that Lenin was a “a very important person from history and we have a lot to learn from him.”

It is a curious phenomenon that Lenin is acceptable and even approved of whereas Hitler is beyond the pale. It is not exactly a secret that Lenin started off 70 years of communist rule in Russia which included two major famines, the Red Terror, the Great Terror and continuing poverty. The death toll of Soviet communism was of the order of 20 million.

So how do people manage to think favourably of him?

The first thing they do is kid themselves that he led a popular revolution removing a corrupt, tyrannical Tsarist regime. This is just not true.

The February revolution could indeed be considered a popular revolution and the Tsar was indeed removed from power. But Lenin took no part in it. He was in Zurich and had to read about it in the Swiss newspapers.

He did lead the so-called October Revolution, later the same year. But that was not a revolution. The fact that it is referred to in Britain as a revolution is one of several ways in which Soviet propaganda has entered British textbooks. In reality it was a coup.

He did lead the so-called October Revolution, later the same year. But that was not a revolution. The fact that it is referred to in Britain as a revolution is one of several ways in which Soviet propaganda has entered British textbooks. In reality it was a coup.

In a rather chaotic series of events, some 10,000 Red Guards took control of Petrograd (now St Petersburg) and arrested the Provisional Government.

Then there is the idea that the coup somehow represented the “will of the people”. We have clear proof that it did not.

The Bolsheviks got only 24 per cent of the vote in the elections to the Constituent Assembly. The more moderate Socialist Revolutionaries received 39 per cent. To put it bluntly, the Bolsheviks lost. But Lenin did not care. Rather like Hitler, whose party incidentally got a higher percentage of the vote in Germany than the Bolsheviks did in Russia, he closed the Constituent Assembly and deployed armed soldiers to prevent anyone reopening it.

The next way to think well of Lenin is to suggest, “If only Lenin had lived, communist rule would have succeeded. Lenin’s replacement by Stalin ruined it all.”

But Lenin did all the things that Stalin did. Lenin began government control of agriculture, setting a fixed price that the government would pay for corn and other grains. The price was absurdly low because of the high rate of inflation. A shortage of food ensued. Lenin then requisitioned grain from peasants at gunpoint. These disastrous policies contributed heavily to death by starvation of at least three million people in 1920-21. Lenin implicitly recognised the part his policies had played by reversing them in 1921.

But meanwhile, Lenin took advantage of the famine to steal from the church, seizing 500 kilos of gold along with a vast quantity of silver and precious stones in November 1921 alone. He stated that this was an opportunity to kill members of the bourgeoisie who resisted this expropriation. “The confiscations must be conducted with merciless determination… the greater the number of clergy and reactionary bourgeoisie we succeed in executing for this reason… [ie resisting church looting] the better.” In two years, more than 30 bishops and 1,200 priests were killed.

Lenin created the Cheka, the Soviet secret police. His on-the-record instructions to kill include this written order following a revolt in Penza Province: “Hang (absolutely hang, in full view of the people) no fewer than 100 known kulaks [peasants owning a little land], filthy rich men, bloodsuckers”. Lenin did not engage in class war. He engaged in class murder.

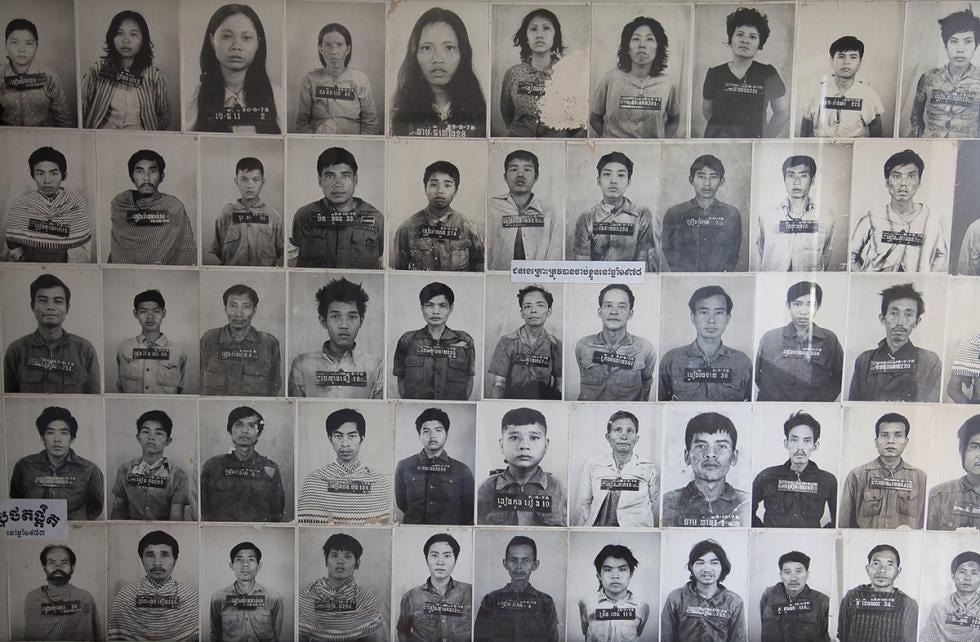

Lenin set up the concentration camps which eventually became the Gulag. He issued a decree in 1918 stating that it was “imperative to safeguard the Soviet Republic from class enemies by isolating them in concentration camps”. Every provincial city was ordered to create one and by the end of 1920 there were 107 of them. Lenin authorised the use of poison gas in 1921 to kill peasants in the Tambov uprising.

Molotov, a senior Soviet politician under both Lenin and Stalin, remarked that both leaders were “hard men…harsh and stern. But without a doubt Lenin was harsher.” Again and again the records show Lenin urging his colleagues to be more ruthless and to kill.

Against all this, the defence is sometimes, “well it was a time of civil war, so extreme measures were necessary”. But why was there a civil war? Only because Lenin had mounted a coup that was contrary to the expressed views of the Russian people. And the clery, for example, were not waging war.

Supporters of Lenin argue that he did some wonderful things. He issued a decree that women should have equal rights in 1917. But it was the Provisional Government that had already given women the vote and it is not as if the Soviet Union was unique in conferring increasing rights to women during the 20th century. It was happening throughout Europe. It is noticeable that the first politburo included no women at all and most people will be hard pressed to think of any woman who ever achieved a major political or business role in the Soviet Union.

There is anyway something grotesque about this sort of argument. It is reminiscent of the well-known justification for Mussolini’s dictatorship in the 1930s: that “he made the trains run on time”. You could say something similar about Hitler: “at least he righted the wrongs of the Versailles Treaty” or “he gave the Germans back their self-respect”. Such arguments are obscene when juxtaposed with mass slaughter.

The final argument is that Lenin was an important historical figure. This is true.

Robert Service, in his biography of Lenin, went so far as to say, “Without Lenin, there would have been no revolution in October 1917. Without Lenin, the Russian Communist Party would not have lasted much beyond the end of 1921.”

But what were the consequences of his success?

Russia endured 70 years of communist rule with all the deaths, the savage torture, the prison sentences and the economic failure this caused. The secondary effects of the coup rippled through the 20th century far more than Hitler’s brief rule. Lenin’s success made Stalin possible. Stalin, in turn, made an alliance with Hitler in 1939 which freed both of them to invade their agreed shares of Poland. Stalin also invaded the Baltic States and grabbed as much of Finland as he was able. At the end of the Second World War, Stalin invaded most of Eastern Europe, leading to more mass deportations, terror and murders. The Soviet Union also encouraged and enabled the communist coups in China, Vietnam and elsewhere. Lenin created a template for similar coups around the world. The Soviet Union gave financial and military assistance to them.

Russia endured 70 years of communist rule with all the deaths, the savage torture, the prison sentences and the economic failure this caused. The secondary effects of the coup rippled through the 20th century far more than Hitler’s brief rule. Lenin’s success made Stalin possible. Stalin, in turn, made an alliance with Hitler in 1939 which freed both of them to invade their agreed shares of Poland. Stalin also invaded the Baltic States and grabbed as much of Finland as he was able. At the end of the Second World War, Stalin invaded most of Eastern Europe, leading to more mass deportations, terror and murders. The Soviet Union also encouraged and enabled the communist coups in China, Vietnam and elsewhere. Lenin created a template for similar coups around the world. The Soviet Union gave financial and military assistance to them.

In short, yes, Lenin was an important historical figure. The communist regimes which emerged in his wake caused poverty, fear, oppression and the deaths of an estimated 80 to 100 million people. He was the most disastrous leader of the 20th century and the damaging effects of his coup continue to this day. His image should be as unacceptable as Hitler’s.

James Bartholomew is the director of the Museum of Communist Terror

More Articles