A little-known part of the history of communism in Europe is an unauthorised, freelance effort by British intellectuals and their friends to create a kind of secret university behind the Iron Curtain.

It was amateur, idealistic and slightly dangerous. It brought a surprising amount of comfort and hope to some Eastern European intellectuals, some of who went on to become prominent politicians. The little groups of Britons managed to involve some of the most prominent people in Britain at the time including Paul McCartney, Elton John and Yehudi Menuhin.

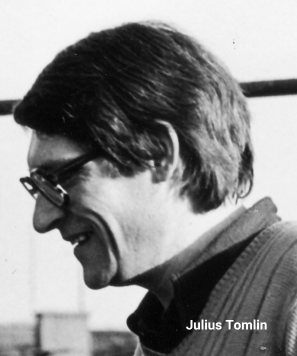

It seems to have started with Julius Tomin, an academic in Czechoslovakia who had been denied a position in any university because of his political views. He conducted secret seminars in philosophy and, in 1979, he wrote to various universities in Western Europe, asking them to send speakers.

The only British university to respond was Oxford. Kathy Wilkes, a tutor at St Hilda’s College, was the first academic to venture into Czechoslovakia to give a talk.

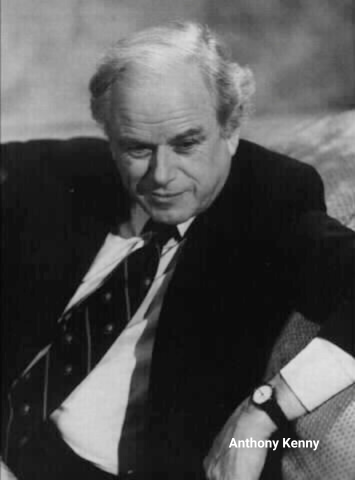

At the hub of the Oxford response was the Master of Balliol, Anthony Kenny. In May 1980, they founded the Jan Hus Educational Foundation – named after a medieval Czech theologian and church reformer. Anthony Kenny himself went out to Czechoslovakia in 1980. He was in the middle of discussing a text by Aristotle when 20 policemen barged in and arrested Julius Tomin. Anthony Kenny himself was interrogated and then thrown out of the country.

Ironically, this incident boosted the Jan Hus Educational Foundation. The incident got into the news and donations poured in.

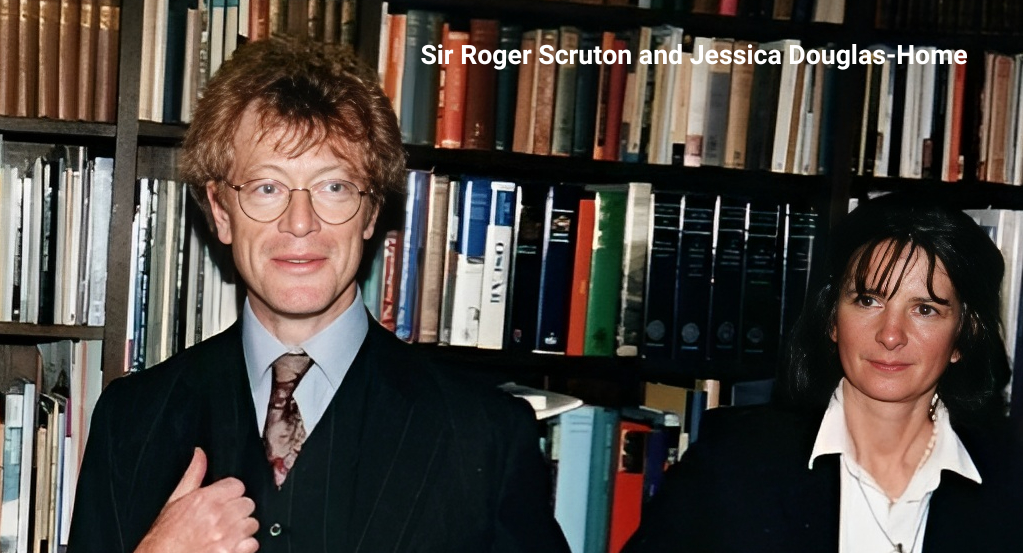

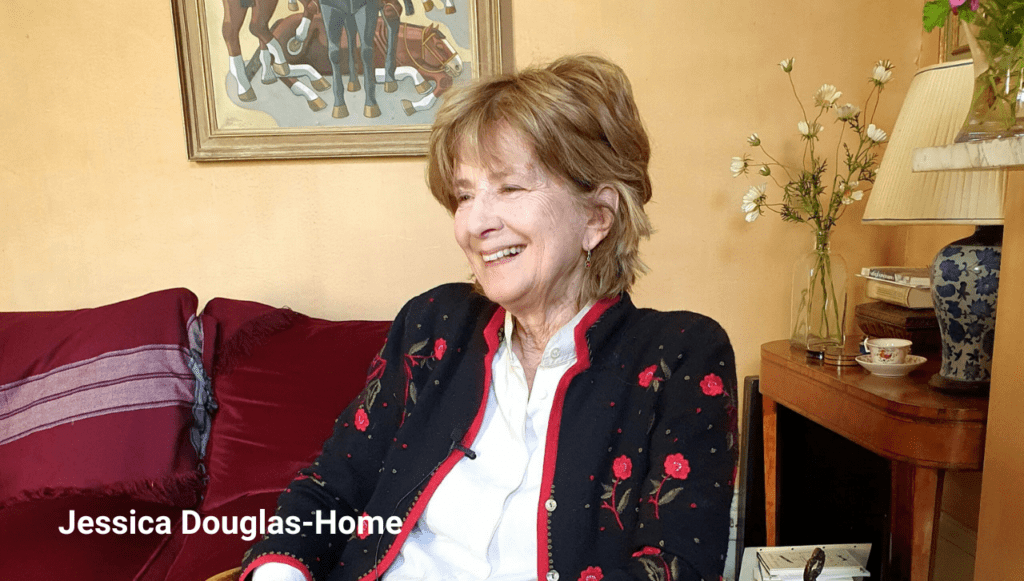

Over time, more British academics and others volunteered to make the perilous journey into Czechoslovakia. One was Roger Scruton – later Sir Roger Scruton – a leading conservative philosopher and writer. Others included Noel Malcolm, Mark Almond, David Pryce-Jones and Jessica Douglas-Home. These volunteers all had other jobs and roles. They found time to do this work because they believed in it. When asked what motivated her, Jessica Douglas-Home said, “anger”. She was angry that academics in Eastern Europe were losing their jobs and sometimes imprisoned because they wanted intellectual freedom.

The British effort has sometimes been described as providing an “underground” or “secret” university. They certainly did offer courses and mark essays. But their work was more than that. They took out books, magazines and articles which were banned in Eastern Europe. They smuggled out articles by Eastern European academics which, from time to time, were published in the British press. This was more important than it might seem because, at that time, there were plenty of intellectuals in Britain who thought of Eastern Europe as an admirable experiment in socialism. The articles helped to correct this image, describing the reality of intellectual and physical oppression. Another thing the British visitors to Eastern Europe did was draw attention in the British and American press to particular cases of repression.

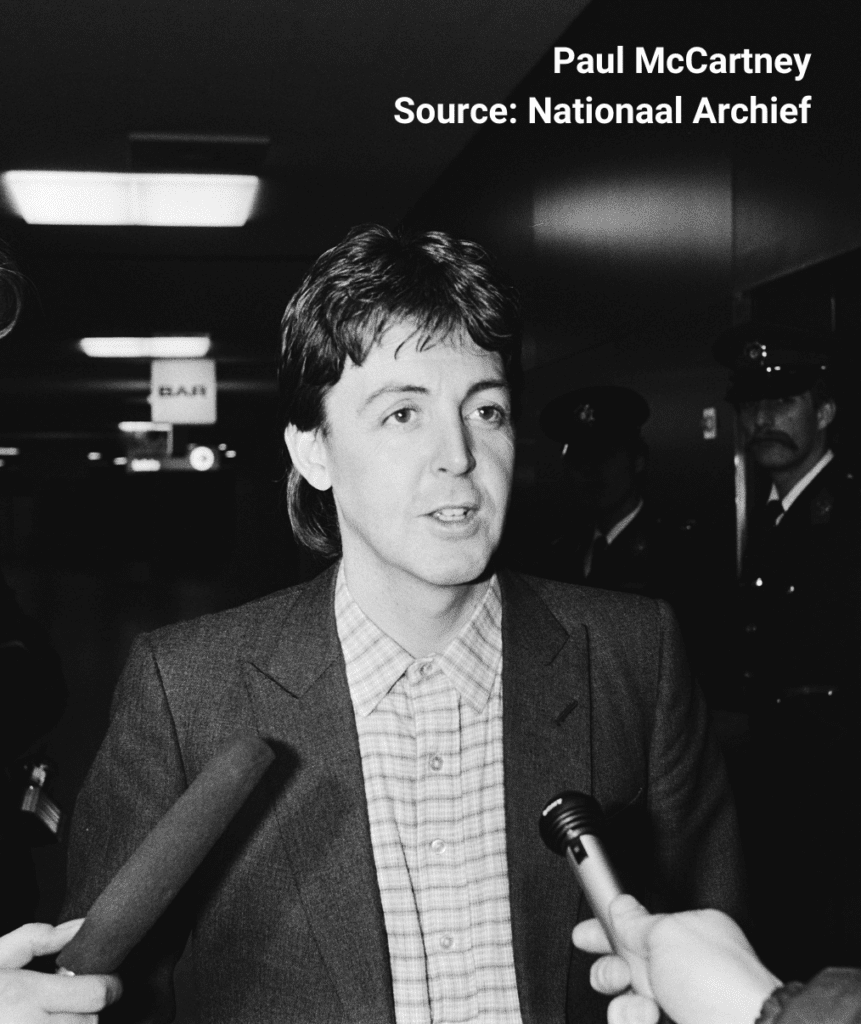

One of these centred on a jazz club in Prague called the Jazz Section which had become a focus for moderately free expression about modern culture. It is a reflection of how keen many Czechs were to enjoy this that its membership surged to 6,000. The Czech authorities did not like this show of cultural independence and eventually arrested and put on trial the manager, Karel Srp. Immediately the Jan Hus Educational Foundation jumped into action. Its trustees and sympathisers arranged for articles to appear in the British and American press. They also got together a petition in support of the Jazz Section. They persuaded a star-studded array of music stars to sign the petition including the virtuoso violinist, Nigel Kennedy, jazz star Ronnie Scott and many pop stars including Elton John, Bob Geldof and Paul McCartney. Paul McCartney added a drawing of a smiling face and the words, “Best wishes to all Czech musicians!!”

One of these centred on a jazz club in Prague called the Jazz Section which had become a focus for moderately free expression about modern culture. It is a reflection of how keen many Czechs were to enjoy this that its membership surged to 6,000. The Czech authorities did not like this show of cultural independence and eventually arrested and put on trial the manager, Karel Srp. Immediately the Jan Hus Educational Foundation jumped into action. Its trustees and sympathisers arranged for articles to appear in the British and American press. They also got together a petition in support of the Jazz Section. They persuaded a star-studded array of music stars to sign the petition including the virtuoso violinist, Nigel Kennedy, jazz star Ronnie Scott and many pop stars including Elton John, Bob Geldof and Paul McCartney. Paul McCartney added a drawing of a smiling face and the words, “Best wishes to all Czech musicians!!”

Eastern European countries at this time cared more than one might expect about their image in the West. So, as a result of this intervention, the preliminary hearing was postponed and it seems likely that Srp received a shorter sentence than he would otherwise have done. And it is also likely that the Czech authorities were made more cautious about prosecuting such people in the future.

One of the achievements of the British volunteers was to mobilise support from those with influence, those who could provide publicity, celebrities, rich donors, politicians including the Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher and even Prince Charles, who made a speech going as far as he could while staying non-political. He argued in favour of the preservation of ancient Romanian villages which, at the time, were being destroyed by President Nicolae Ceaușescu in Romania.

The patrons of the Jan Hus Educational Foundation included many of the great and good of the time including Yehudi Menuhin, the violinist, and Harold Pinter, the playwright. The trustees included the novelist Iris Murdoch and Tom Stoppard, another leading playwright.

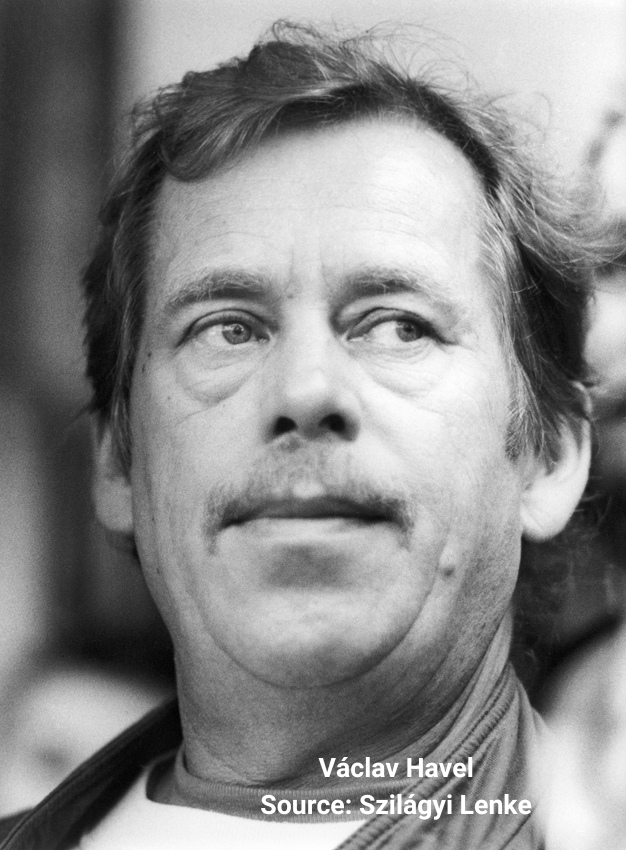

In the course of their activities, the British activists were in contact with many Eastern Europe intellectuals who became important politician. Vaclav Havel became the president of Czechoslovakia after Communist rule there collapsed peacefully in 1989.

The British effort started in Czechoslovakia but soon spread out to Poland and then into Hungary and Romania. Were their trips dangerous? At the time, they could not be sure what might happen.

Returning from a trip to Poland in 1985, Jessica Douglas-Home went up to the passport control at Warsaw airport and was approached by a man in a grey suit who told her to follow him. He took her to a room where she was met by a thick-set, surly woman who said she was going to search her. Jessica had on her details of contacts in Poland. They were in code but she was worried about betraying her contacts. She started tearing up the paper on which the details were written and swallowing them while at the same time physically fighting off the attempts of the official to stop her.

After this fracas, she was nevertheless let out of the country. And, indeed, generally the Britons who were arrested on these missions to Eastern Europe, were let out after some interrogation. Sometimes they were banned from returning to the country concerned. The Eastern European intellectuals they tried to support were not so lucky. At a minimum, they would lose their jobs in universities if their activities were discovered. The next thing would be arrest and perhaps a term in prison. A few were subjected to house arrest.

The British visitors had to learn some spycraft: how to detect if they were being followed; how to shake off someone following them and how to communicate with dissidents in homes and restaurants which were bugged. They would write notes to each other and go out of doors.

What was the British establishment’s attitude to the efforts of these British volunteers? It was often quite discouraging. Most British universities preferred to maintain ties with the official communist-approved universities in Eastern Europe. The volunteers made a point of letting the Foreign Office know about their visits but it became clear that the Foreign Office regarded their work as “unhelpful” – presumably unhelpful in that it disturbed their work in trying to build bridges with the regimes that were oppressing their own people. It was only towards the end of the 1980s, when the communist regimes were crumbling, that the Foreign Office suddenly became much more supportive of Roger Scruton and his associates.

Did their efforts achieve much? The communist regimes themselves certainly seemed to regard them as a threat. Jessica Douglas-Home later got access to the file kept on her by the Securitate, the Romanian secret police. One report on her activities referred to her as “a very dangerous lady”, a description which delighted her, of course.

By supporting independent thinkers in Eastern Europe, it is possible that they played a small part of the way in which those countries came to accept that communist rule had made them into closed, paranoid societies rather than ideal socialist states. They also contributed to making the West more aware of the true nature of the communist regimes. They definitely gave succour to individuals in Eastern Europe who were isolated and oppressed. This was surely a noble thing of itself. And the fact they did this work voluntarily was surely gallant and admirable. The whole effort is unusual in Cold War history because it was entirely amateur and self-starting.

In October 1998 at Magdalen College, Oxford, President Václav Havel awarded the Foundation, Kathy Wilkes and Barbara Day Commemorative Medals of the President of the Republic. Roger Scruton was awarded the Medal of Merit (First Class) of the Czech Republic.

This is the tribute of Pavel Bratinka, a Czech academic who was thrown out of his normal career and was obliged to become a boiler-stoker to earn a living:

They were a very diverse lot. Some were believers, others atheists. Some were right wingers, others belonged to the left. They were coming to give lectures, bring books and smuggle writings and messages from us back to their lands. We did not necessarily agree with all of them. But the thrill of having an opponent [ie an opponent of totalitarian rule] who really believes what he is saying and who believes the same about you was an ambrosia for us who lived in a totalitarian environment where anything else than parroting the Big Brother’s lie was dangerous…

The sources for this article were Once Upon Another Time by Jessica Douglas-Home, her article in The Critic The secret university | Jessica Douglas-Home | The Critic Magazine in May 2021 and a video interview by the author with her in June 2023. Additional sources were a video interview with Pavel Bratinka in Prague, a conversation with Barbara Day in Prague and several conversations with the late Sir Roger Scruton. Details of the Jan Hus Educational Foundation are from the Wikipedia entry on the subject: Jan Hus Wikipedia page. Jessica Douglas-Home is a trustee of the Museum of Communist Terror and Sir Roger Scruton was a trustee until his death in 2020.